The Quickie Q2

March 2017 - In the late ’70s and early ’80s, I was working with the Canadian distributor of the Quickie and the Q2 and, in the earlier days, had no flying experience but lots of building time. We built the first Quickie in Canada and eventually developed it into the two-seat model known as the Q2. 1981 saw me at Skyways in Langley, British Columbia, working on a private licence. After about 70 hours total time and less than three hours on a CP65 Porterfield for taildragger experience, in my blissful state of ignorance, I undertook to fly a Quickie Q2.

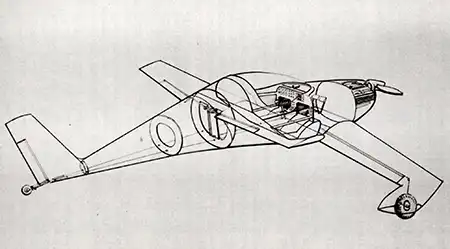

The Quickie Q2 plan

The Q2 was a relatively high-performance two-seat composite plane with very responsive controls and an unusual layout. Sort of a negative stagger biplane to stretch a point. This particular aircraft was the production prototype that had been built to “proof” the kit and was powered by a Revmaster 64-hp engine. It had a fibreglass and epoxy structure and a canard layout with the elevators on the front and the ailerons inboard on the rear upper wings. A powerful trim tab on the vertical fin provided assistance to the elevator. This particular trim was a prototype installation using a Bowden cable to drive the tab. The control knob was located in the centre of the instrument panel, right where the throttle is on a C150 (the Q2’s throttle is on the left side of the fuselage). The Q2 has a side stick controlling pitch and roll. This is positioned between the pilot and passenger seats, and one flies with the left hand on the throttle and the right hand on the side stick.

An example of the Q2

On my first flight, I took off southbound from Mojave airport, a former Marine Corps base located in the Mojave Desert near Palmdale and Edwards Air Force Base. Even though I had been briefed on the sensitivity of the controls, I overcontrolled on liftoff by pulling back too hard on the stick and pitching up way too high and then overcorrecting, thus getting a terrific view of the runway immediately ahead. I managed to sort that out without actually hitting the ground and then continued to climb out southbound. In fact, at that point I was so afraid of overcontrolling that I didn’t do anything except climb straight ahead. As my heart rate got back to somewhere near normal, I figured that it was time to try some turns before I ended up in Los Angeles.

I found the Q-2 to be very responsive in all axes. Gentle banks and turns seemed to be accomplished merely by thinking about them. Visibility through the huge canopy was almost unlimited. Bank left to get the canard out of the way, and you can see straight down.

After experimenting with climbs and descents, turns in both directions, and a little bit of slow flight, it was time to try landing this little beast. I had been briefed on two things. One: Do not try a full-stop landing on the first pass. In fact do at least three touch-and-goes. Two: If you bounce it, don’t do anything. Just sit there with the stick back, and it’ll bounce twice more and settle on.

I flew quite a long downwind in order to prepare for a long final to give me time to sort things out. The approach was steady and the rate of descent was looking quite good. However, I bounced it just like he said I would. I sat through all three bounces with the power at idle and the side stick aft just like I was told to. This is where things got less than pleasant. When I added power to go around, I reached for what, in my limited experience, was the throttle, and I pushed in the big black knob in the middle of the panel. Instead of power, I got full nose down trim. Of course the engine stayed at idle and the tail rose up until the prop hit the runway and everything slid to a noisy stop. That flight ended with a broken prop and dented spinner, scuffed wheel pants and engine cowling, and a severely damaged ego. All before 9 a.m.

I eventually put about 25 hours on the Q2, operating it off a 2,000-foot runway. I came to love most of the handling characteristics except the one involving canard contamination. If the canard got wet or gathered any amount of bugs, it lost about 25 percent of its lifting capability. Since the canard carried about 50 percent of the flying loads, that was a significant loss of lift. This would also occur when flying into rain. Your first indication of a problem would be that you would get about a 5-pound pull on the stick and an immediate pitch down. In order to maintain level flight you would apply full power and full back trim. This made the approaches exciting because of the higher speeds involved. One quickly learned to stay out of the rain and off grass runways.

The problem was ultimately eliminated by either a redesign of the canard to one with a less critical airfoil or by adding vortex generators to the existing canard.

The controls in the Q2 are very light and powerful. This resulted in a control response that exceeded any other homebuilt or factory-built aircraft that I have flown since. Steep turns with a minimum of 45 degrees of bank were the norm simply because it was so much fun. Bank and yank were the order of the day. A bob weight on the elevator increased stick force as the g-load increased, and this automatically discouraged one from pulling too hard. As the speed increased, the controls got progressively heavier or stiffer. Elevator trim on the company demonstrator was controlled not by the elevator but by a small T tail on the vertical fin. This was a very powerful control and very useful in controlling approach speeds and in maintaining pitch control if the canard became contaminated and, as a result, lost lift.

Ground loops could be noisy and exciting affairs but rarely damaged anything other than the ego. The main wheels were 22 feet apart on the ends of the canard and, with the lightly loaded tail wheel, there was little likelihood of tipping over. I’ve heard of ground loops at speeds up to 65 mph but can personally attest to only 20 mph. Stalls essentially couldn’t occur due to the canard configuration. With the engine at idle power, flight with the stick full back resulted in a mild pitch bucking motion and a 200-300 feet-per-minute rate of descent. A reapplication of power resulted in level and stable flight.

Landings should be three-pointers, and this was easily accomplished from an approach speed of 85, slowing to 70 over the fence, with touchdown at 65 (stall) in the first quarter of a 2,000-foot runway. Two thousand feet was about the minimum length for landing due to the low drag of the fuselage and the somewhat marginal brakes. The darn thing just didn’t want to slow down.

Cruise power gave an indicated airspeed around 165 mph, which was good for a 64-hp VW-derived engine.

Unfortunately, the kit supplier has gone out of business, and a nice little aircraft has virtually disappeared from the scene.