Car Surfing With a Cub

Alabama Boys add their own spin to a classic air show trick. By Pete Muntean.

By Pete Muntean, EAA 1066346

From February 2016 Sport Aviation (be sure to watch the video further down the page)

With his hands at 10 and 2 on the wheel of a Dodge Ram pickup, it’s just another day for Fred Masterson. He’s in fifth gear, cruising at a reasonable 55 mph. His driver’s side window is down—but something is off. Through the flapping of the Wisconsin air, you can start to hear a buzz. It gets a little louder (maybe it’s a lawn mower?) followed by a loud burst.

“Okay, he’s on,” exclaims an unrattled Fred as the rear of the truck bounces like somebody just jumped into the truck bed.

But that’s no person, it’s a plane—a stock 1946 Piper Cub piloted by award-winning air show pilot and aerobatic flight instructor Greg Koontz.

“He’s in! That right wheel is coming up—stay down! Stay down! Stay down!”

Greg, with the help of Fred, has just landed his airplane on top of a speeding pickup truck in front of 100,000 people, and I’m an accomplice; a crucial accomplice.

Fred is now gently decelerating to a stop. Before I can even start thinking about my assigned task (we briefed this only an hour ago), I’m out of the truck, standing on the Oshkosh runway, slinging a rope around the Cub’s right wheel. This is where things start to get hectic.

“Don’t let that wheel come up!” Greg yells sitting in the idling Cub now proudly perched atop the mesh aluminum platform welded to the top of the truck. On this Friday of EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2015, there’s a strong crosswind grabbing the right side of the Cub and lifting it like a sail.

Clearly not as proficient at tying knots as I promised in our briefing, Fred rushes over and grabs the rope out of my hands and securely lashes the Cub to the truck frame.

If you’re an average reader, it took you about a minute to read that. All the exciting stuff happens in less than half that.

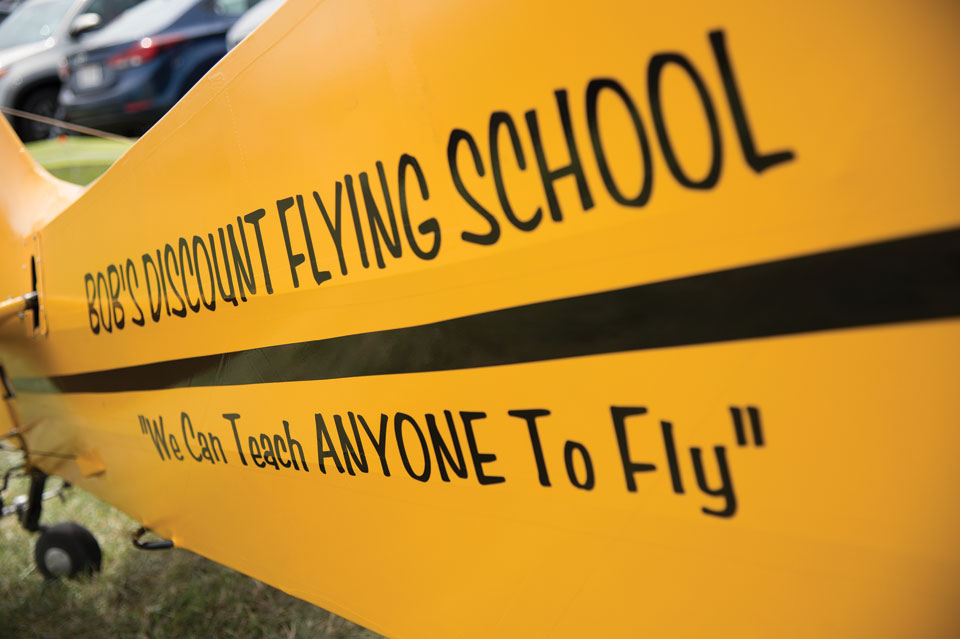

“We do this at 20 shows a year,” Greg says. It is part of a comedy air show act entitled the Alabama Boys. Greg, dressed in raggedy overalls as farmer Clem Cleaver, climbs onto the announcer’s stand demanding his discount flying lesson.

“It looks really animated,” says Fred, who plays the role of Clem’s rifle-toting grandpa. “When we’re doing our ground act we’re trying to make it look chaotic,” he adds. Fred joined Greg as a truck driver (he also trailers the Cub, after removing its wings and half of its tail, from show to show) just a few years ago.

Clem, through his deep Alabama drawl, reasons with the instructor while Grandpa walks to the back of the Cub and lifts the tail over his head. “I always look toward the crowd, and there’s not a kid out there whose mouth isn’t open and their eyes aren’t as wide as dinner plates,” Fred says.

Then, Greg barrels into the Cub, jams in full power, and takes off, slamming the controls to the stops and swooping at the ground.

In an attempt to get Clem back on the ground, Grandpa fires a baby-powder-filled blank at the airplane. Greg drops a tire out of the Cub’s horizontal-split door to make it look like Grandpa actually hit his mark. In a few minutes, Grandpa will race his truck out onto the runway to rescue Clem.

In the airplane, Greg’s loops and rolls are his take on the often duplicated “flying farmer” act. Even this seasoned aerobatic performer says perfecting this routine’s car-top landing finale has been his biggest challenge.

“There’s a technique to doing it,” Greg says. “I found mine by watching other people.” Forty years ago, as part of air show legend Jim Moser’s traveling flying circus, Greg learned a set sequence was key. “We didn’t use handheld radios because they weren’t popular back then. You knew what you had to do, and you did each step. I kind of took that and modified it my own way.”

As Greg dives the Cub behind trees to gasps from the crowd, Fred drives the truck to a predetermined spot on the runway. “He sets where he can see me coming,” says Greg. Just like the olden days, Greg and Fred don’t make radio calls, and Greg says it can make things more chaotic and confusing. “I always make a same-speed traffic pattern giving him a constant so he knows how long it’s going to take me to get there.”

Then, Fred guns it to 55 for the first pass. Timing is crucial. If the truck starts rolling too soon, Greg will never catch him. If Fred starts too late, Greg can only decelerate so much before he stalls. “It’s a fairly narrow envelope. We’ll blow by the crowd trying to coordinate.”

Greg and Fred do one pass with the wind at their backs “to make it look hard,” Greg says. “That’s called showmanship.”

Now turned into the wind, Fred tracks the centerline of the runway, and sets his speed. Then Greg takes control. “It’s my job to get behind the truck and get on the truck, then roll forward and fall into the wheel wells,” he says.

Recessed divots in either side of the platform do two things: They keep the plane from rolling forward (and off the ledge of the platform) and lower the angle of attack of the wing (making it harder to fly away). “I’ve got the tail high at that point, and I can just push in,” Greg says.

With precious remaining runway, it’s once again Fred’s turn to take control. He starts decelerating the truck. If not, that’s Greg’s signal to pull back on the stick and climb away for another attempt. “If I see he hasn’t slowed down in a matter of a few seconds, he’s telling me he’s not going to stop,” Greg says. “Probably because I’ve been intensely trying to land on this platform and I’ve forgotten we’re running out of runway,” he says with a chuckle. If there is enough space, Fred gently brakes, careful not to dump Greg off the top of the platform.

“There’s days we’re trying to make it look hard, and some days it’s just hard as hell.”

Today, they’re not faking anything.

With a hearty, gusty crosswind as we hurtle down Runway 18, I can see Greg through the side-view mirror jockeying the stick and throttle as he inches toward the truck platform.

“I’ll be moving toward that truck and go, ‘Man, I’ve got this lined up!’ And then I’ll get within 3 feet and all hell breaks loose,” he says. “Sometimes it’s like trying to put two magnets together.”

Now craning my neck high and right, I watch Greg hit one big bump—a combination of turbulence from the truck and the wind—just before the tires hit the makeshift metal runway.

From this vantage point Greg’s corrections are noticeable but small. He doesn’t make exaggerated, one-wing-low crosswind approaches. “You land in a crab, then you kick it straight and roll to the front,” says Greg. “I’ve also learned to use adverse yaw in the ailerons and make it work in your favor. When you’re out there skidding, you’re using that aileron drag like a rudder. That’s taught me a lot about what taildragger flying really is,” he says. “It’s not a landing at all. You get in formation with the truck and then plant it on.”

Today, that’s exactly what Greg does—makes the difficult look easy, yet again—an homage to the early barnstormers who pioneered acts like this. IAC Hall-of-Famer Mike Murphy is credited with inventing the car-top landing in the 1930s when he landed a Cub on top of a car with a wooden rack. In the 80 years that followed, the act has been often duplicated. In addition to Greg, Kent Pietsch of Minot, North Dakota, lands his 1942 Interstate Cadet atop a speeding motor home.

“We are by no means the original on this. I’ll walk into an FBO and see a photo of a Cub landing on an old Chevy,” Greg says. “It’s a good old-fashioned act, and it adds a good variety to a show.”

The act is so closely associated with the Piper Cub that three years ago the organizers of the annual Sentimental Journey Fly-In at the former Piper factory in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, asked the Alabama Boys to perform. “It was the 75th anniversary of the Piper Cub (and) was a huge deal to me,” Greg says. “We would have done it for free, but they paid us!”

After landing, Greg shuts down the engine and hops out onto the platform, yeehawing and waving at the crowd with his worn ball cap while Fred blasts “Sweet Home Alabama” before driving into show center.

Typically the duo sets up a table in the crowd, especially at smaller shows, and gives away posters. “We get a lot of kids coming up wanting to know all about it,” Greg says. “Now I have some coming up to me saying they first saw the act a few years ago and now they’re teenagers getting ready to solo.”

As Greg and Fred bring their act to a close, the United States Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier launches into its deafening hover from an intersection taxiway, then AC/DC blares over the PA system. “High energy excitement is very important to air shows,” Greg says. “But you have to remember it’s entertainment. You can be the best pilot in the world. You can fly a crisp, perfect show. But you have to be entertaining.”

------------------------------------------------------------

Pete Muntean, EAA 1066346, supports his third-generation flying habit as a freelance aviation writer and television reporter covering Pennsylvania politics. He flies a Super Decathlon in regional aerobatic competitions.