The Rest of the Story: High Flyin' Tiger

Story and Photographs by Brett Hahn

June 2016

“There’s no magic formula for overcoming great obstacles and realizing your dreams. Surround yourself with the best and don’t give up. You will succeed.”

—Exxon Flyin’ Tiger pilot Bruce Bohannon

Angleton, Texas—Bruce Bohannon sat in the cramped rear cockpit of his highly modified RV-4 named Exxon Flyin’ Tiger. Steadily he drew in another lungful of 100 percent oxygen through the rubber mask strapped to his face. Over the next hour and a half, Bruce would repeat this ritual 900 times. He was preparing to go into the stratosphere, an attempt to climb the Exxon Flyin’ Tiger to almost 50,000 feet and surpass the all-time U.S. altitude record for a piston engine airplane, set by an Air Force B-29 bomber in 1946. The B-29 crew went to 47,910 feet; to break their 59-year-old record and set a new one, Bruce had to surpass it by 3 percent, going to 49,347 feet.

As he continued to breathe the pure oxygen, his crew chief, Gary Hunter, bustled around, monitoring Bruce’s progress and making last-minute system checks. Bruce was dressed for the frigid cold he was about to encounter. He had donned long underwear, jeans, and a two-piece, electrically heated motorcycle-riding suit that plugged into the aircraft’s electrical system. Gary signaled Bruce—the time had come.

Gary handed Bruce the battery pack, a small unit that is used to start the Tiger, as it only carries a very small battery on board (a victim of Gary’s ongoing weight-reduction program). Bruce plugged in the battery and started down his checklist. He gave Gary a thumbs-up and cranked over the engine. It caught instantly and roared to life. Bruce pulled his straps tight and snapped on his helmet. As the engine warmed up, Bruce slid the canopy closed and looked at Gary one last time, more a nod of approval. Bruce advanced the throttle forward and taxied out.

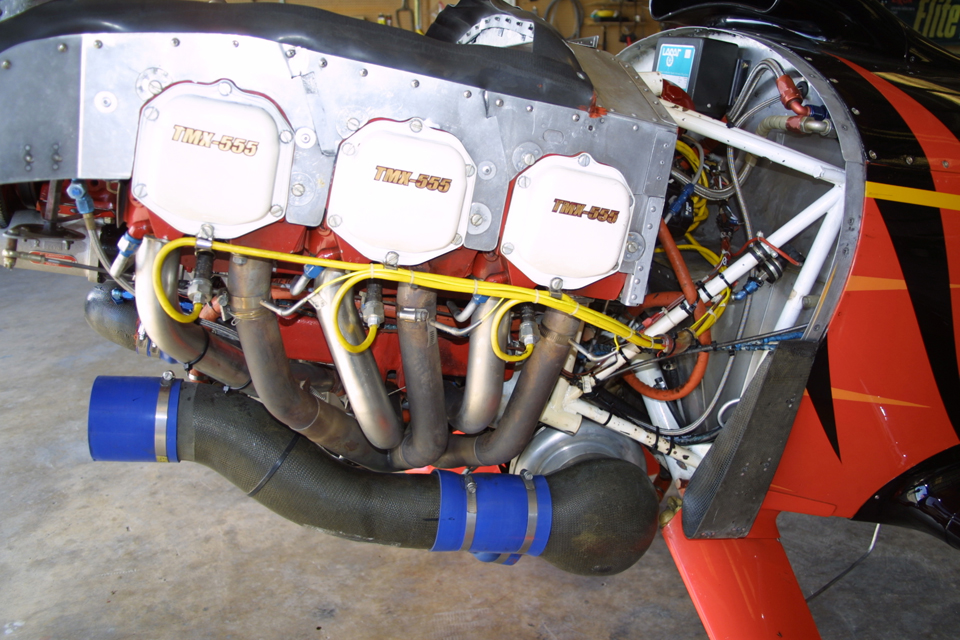

Moments later the Exxon Flyin’ Tiger was clawing its way up through the thick Gulf Coast air, putting better than 2,000 feet under its belly every minute. The stroked, turbocharged, and intercooled Lycoming IO 555 built by Mattituck was pumping out 380 hp. The tach read 2950 rpm. Bruce reduced the power to 25 inches squared to manage cylinder head temperatures; the big LYC was burning better than 25 gallons per hour.

The little town of Alvin, Texas, provided a great environment for Bruce to grow up in. Just north, the skyscrapers of downtown Houston loomed large in his view. The Bohannon family lived a short distance from a crop-dusting strip and Bruce would wake up to the roar of Ag Cats and radial-engine Stearman biplanes as they danced in the early dawn skies. That strip beckoned this 12-year-old kid on a bicycle like a moth drawn to a flame. Bruce fell in love with flying at that old grass strip. He watched the airplanes’ every move, smoke belching on start-up, taxi, and takeoff. He marveled at the pilots as they plied their trade, twisting and turning, flying just feet above the crops only to zoom up at the end of each row, narrowly missing fences and utility poles. Could there be a better job in the world? Bruce could not imagine any.

In 1976, at the age of 16, he soloed in a Cessna 150 at Houston’s Hobby Airport. He could fly now! After getting his private license, Bruce built up as much time as he could and started looking for a crop-dusting job. However, none were to be found. He was at the bottom of the totem pole; there were no jobs for a no-time crop duster. Finally, he got a chance to fly the Ag Cats and Stearmans. Bruce spent the next 10 years making a living dusting crops from Texas to Mississippi.

About 10 minutes into the climb, Bruce passed through 25,000 feet. The outside temperature now was a balmy 28 degrees below zero, even though he had launched at noon. The ambient air pressure had dropped from 14.7 psi at sea level to 5.5 psi. The huge Kelly Aerospace turbocharger was really huffin’, pressurizing the manifold pressure up to 11 psi (25 inches of mercury).

Bruce thought about the last flight. He had a massive oil leak and had to dead stick it in. On another record attempt, the fuel tank vent tube froze shut at 44,000 feet. As he descended, the difference in pressure crushed the tank and killed the engine—another dead stick landing.

Not today though. The Exxon Flyin’ Tiger was running sweet. At 25,000 feet, Bruce switched the pressure-demand oxygen system to pressure breathing. Oxygen was now being forced into his lungs. Exhaling was a struggle. Still, Bruce climbed upward over the Gulf of Mexico.

Crop dusting was seasonal, a tough way to make a living. In his late teens now, Bruce began to fly aerobatics at air shows in a Pitts Special to supplement his income. The pay was sporadic but Bruce loved what he was doing. He started teaching aerobatics and met Jim Robinson, a local oilman with a serious penchant for flying. They hit it off right away and Bruce started Jim’s aerobatic lessons. Jim was slow to learn what came so naturally for Bruce and it was frustrating for both. Eventually Bruce got Jim up to speed in the Pitts. For Jim it was payback time.

One hot, humid day, Jim confronted Bruce about his career. He told Bruce he was capable of so much more than dusting and an occasional air show, but Bruce did not have a hearing for Jim’s advice. Jim made Bruce an offer: He would hire Bruce for one year and teach him how to fly the oil company’s airplane, a Hawker 600 (an eight-passenger, 495-mph jet). Jim would pay Bruce $30,000. At the end of the year, he would terminate the contract. Bruce jumped at the chance.

Bruce’s first look at the Hawker 600 cockpit had him reeling from techno-shock. It was wall-to-wall instruments, gauges, and switches. He was overwhelmed by the complexity and considered bolting, but Jim calmed him down and had him sit in the left seat.

“This is the climate control panel,” Jim said quietly as he pointed. “These knobs control the cabin pressure, and these knobs control the cabin and cockpit heating or cooling. It is all automatic; just set it and forget it. This panel down here is the flight director. You put in the flight plan, waypoints, and such and hit the autopilot switch on the control yoke here. Try it, Bruce; type in the identifier for Houston Intercontinental Airport.”

Bruce typed in “KIAH” and hit the enter button. The display lit up. Bruce smiled. “It’s not so hard,” Jim said.

It was getting cold now. Bruce was climbing through 30,000 feet. The airspeed indicator read 110 mph, although the GPS read 176 mph. The outside temperature had dropped to 50 degrees below zero. He reached down and turned the heater rheostat on his electric suit all the way up. It did a reasonable job of keeping him warm.

His climb rate was starting to drop now; it was down to 1,500 fpm. Bruce scanned the gauges and adjusted the prop speed so the tips would not go supersonic. Every 5,000 feet, he ritually reduced the rpm by 50 to compensate for the dropping speed of sound, which was now only 1,017 feet per second. Bruce leaned the fuel injection a bit more. Now everything looked good.

Over the next three months, Bruce knocked out an instrument rating while learning the Hawker Jet inside and out. Jim provided a clothing allowance and bought new uniforms for Bruce. A crop duster’s overalls would not cut it in the upscale world of corporate aviation. Within six months, Bruce would fly the Hawker Jet all over the United States, responsible for checking weather, flight planning, supervising refueling, and ordering food.

“It was one of the most important periods of my life,” Bruce reflected later. “When I met Jim, I was just an ole’ hillbilly crop duster. He helped me gain confidence in myself and broke through my self-imposed learning disability.” True to his word, after one year Jim terminated Bruce’s contract. Bruce kept the uniforms.

Bruce learned to fly helicopters and eventually settled down and got married. Having two kids turned Bruce into a family man. He became the consummate Mr. Mom and raised two wonderful boys.

The year 1989 brought on an unlikely partnership between Robert Gibson and Bruce Bohannon as they shared hanger space at Clover Field in Houston. Astronaut Robert “Hoot” Gibson would later command shuttle flight STS 71 (his first of five missions), docking the Shuttle Atlantis for the first time at the International Space Station. In their off time, they wanted to race at the Reno National Championship Air Races in the Formula One Class. They teamed up and raced Cassutt racers in the early days, then later raced a new pusher called Pushy Galore. In 1989, Bruce was awarded International Formula One Rookie of the Year.

In 1991, he was awarded the Bill Skliar Memorial Award for outstanding contribution to air racing. In 1993, Bruce received the Bob Downey “Ole Tiger” Memorial Trophy for the most inspirational competitor. Bruce raced Pushy at Reno for 10 years, as well as tackled numerous FAI time-to-climb records. Bruce set his first U.S. and world time-to-climb record in Pushy Galore in 1994 (6,000 meters in 12 minutes, 50 seconds, Class C-1.A, Oshkosh, Wisconsin).

By adding nitrous oxide injection, Bruce breathed real fire into Pushy Galore’s little 4-cylinder O-200. The stock Continental only put out 100 hp. However, with the nitrous, it made in excess of 250 hp and would climb at 4,000 feet per minute. Bruce would race anybody for cash, from a dead start to 3,300 feet, and lost only one race, to the late Jimmy Rossi. Rossi was flying an after-burning Russian MIG-17 and defeated Bruce only after Pushy suffered a nitrous malfunction. Bruce was also the three-time champion of the AeroShell 3-D Speed Dash (1996, 1997, and 1998). Pushy Galore retired in 1998 and is now on display at EAA AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh.

Twenty minutes into the numbingly cold flight, Bruce climbed through 40,000 feet. He did not know it yet, but he had just shattered his previous 12,000-meter time-to-climb world record by almost two minutes. The newly modified wings were 3 feet longer. They seemed to be working well, even though the Tiger was less responsive. Bruce grinned with confidence.

The outside temperature gauge read 70 degrees below zero. When Bruce reached 25,000 feet, moisture from his exhaled breath froze on the canopy. Now at 40,000 feet, his breath turned to snow!

Bruce had done a lot of things in a cockpit, but this was the first time he ever “snowed.” He could see nothing at all, but visibility was not a factor, as his autopilot was engaged, taking care of the steering chores. Bruce trimmed for best rate of climb and the airspeed indicator sank to 105 mph. The GPS read 189 mph. A GPS failure on a previous flight forced the team to enclose the GPS unit in a sealed box, because the severe cold and low air pressure at high altitude caused it to malfunction. He looked at the gauges and leaned out the fuel injection system some more. The engine was burning 12 gph now, with only 9,300 feet to go.

In 1999, a divorced Bruce Bohannon bought an abandoned airport outside of Angleton, Texas, for him and his kids to live on. It had been repossessed and Bruce worked a deal to owner-finance. It was 53 wooded acres of live oak trees and two grass strips running north and northwest, diverging like a V. Hundreds of birds nested there and deer roamed the woods. A creek ran through it.

Bruce renamed it Flyin’ Tiger Field and moved his operation into the 50-by-100-foot hangar. He later purchased 40 additional acres as a buffer zone against societal intrusion. Bruce chose a beautiful location for a new home site and built an earthen pad that rises up and affords a majestic view. Inside the V of the two perfectly manicured turf strips sits a lake with an island in the middle. On the island, an orange windsock sways.

In addition to the Tiger, Bruce acquired an old Piper Cub that he uses to keep his flying skills sharp. Every week as a part of his routine, he cuts the engine and practices dead stick landing...every week.

The altimeter was now reading 47,000 feet, just 910 feet to go to tie the U.S. altitude record. Bruce had been climbing for more than 45 minutes, but as the GPS read 47,020 feet, the Tiger stopped climbing. Bruce scanned the gauges, looking for trouble. The engine, even though it was screaming away at 2300 rpm, was only making a pitiful 125 hp. The cylinder head temperatures were hot, hovering around 525 degrees F. The oil temperature was inching toward a critical 260 degrees. At that oil temp, the prop governor could malfunction, causing a dangerous over-speed. The turbocharger intake temperature read just less than 1,800 degrees F. The huge intercooler mounted under the snorkel-like hood scoop was trying to do its job ejecting heat. The inlet manifold air temp was well under the maximum 100 degrees. Bruce shook his head.

Bruce was smitten with Donah Nevill, a journalist who for years covered Bruce’s aerial escapades for KPRC Radio and Channel 2 television in Houston. Bruce taught her to fly taildraggers. Together they learned the noble sport of sky diving.

On a blustery Saturday morning in April of 2001, Bruce coaxed Donah to take the leap of her life. Although it was a bit windy for Donah’s taste, the pair drove to the local drop zone for a day of sky diving. As they boarded the twin Otter at Skydive Spaceland, Donah fixated on the gusty wind and how she would fly her approach pattern. A sky-diving videographer plopped down on the bench next to her and asked if he could tape their exit. “Sure, whatever,” she mumbled, concentrating on her wind worries.

As the Otter climbed out, Bruce outlined a jump plan for the group of three, including various docking and turning maneuvers. “Yeah, okay,” Donah replied, barely hearing him.

At 13,500 feet, the couple exited together with the cameraman in hot pursuit. Instead of docking with her as planned, Bruce tumbled out of control as Donah watched, bewildered. When she saw the videographer lurking beside Bruce, she thought, “Okay, he’s clowning for the camera. Okay, I can do that.” She flipped onto her back and began spinning. Meanwhile, Bruce, clutching a slip of paper, was literally fighting for stability.

Finally, he closed his left hand to match the right and managed to dock with Donah. Arms and legs tangled as Bruce struggled to unfurl the note in his hand. Her eyes widened as she read, “Donah, will you marry me?” With the world rushing up at 120 mph, there was just enough time for a nod and a pull. The question hung in the air as their two canopies floated silently to the ground.

Back on terra firma, a crowd of friends rushed around the couple. Somebody yelled, “Bruce, what did she say? What did she say?”

“Hell, she didn’t say nothin’ yet,” Bruce replied as he ripped off his goggles. Surrounded by witnesses, Bruce walked over and asked Donah, “Was that nod a yes?”

Donah smiled, “That was a YES!” There was no turning back now. The photographer got it all on tape.

The big paddle blades of the specially designed 80-inch Hartzell prop were spinning around at Mach .89, but there was precious little air to bite into. The ambient pressure was less than 2 pounds per square inch at this altitude, down from 15. Bruce adjusted the mixture and tried to fly slightly faster, but the Tiger just mushed and lost altitude. He slowed down to his best lift-over-drag speed (L/D) of 105 mph and nursed the Tiger higher. The GPS read out 240 mph. Now the Exxon Flyin’ Tiger was parked at 47,020 feet.

Bruce had one last card up his sleeve. Unison Industries, one of his oldest sponsors, was about to save the day. For the first time in 36 world attempts (in Pushy Galore and the Exxon Flyin’ Tiger), Bruce had asked Unison Industries to modify its ignition system. Unison obliged, with a variable-timing ignition that was manually adjustable from the cockpit. Saving this option for last, Bruce advanced the timing and the engine growled with a tiny bit more power. The altimeter inched upward. Fifty-one minutes into the flight, he focused on the GPS. It now read 47,530 feet.

Control was good, she felt good, but the Tiger just would not climb any higher. The wing extensions had netted him nothing, but by manually advancing the timing, he was able to coax Flyin’ Tiger from 47,020 to 47,530 feet! Unison’s ignition system was directly responsible for that last 510 feet. Bruce was only 380 feet below the Air Force B-29 altitude record and just more than 1,800 feet away from setting a new U.S. altitude record.

Bruce silently thought about the magnificent job that the crew had done. He thought about the fans and the great sponsors. They all believed in him—their hearts and minds were all up here with him right now. It was time to go home. He pointed the nose down and started to descend. An hour later, he touched down at Flyin’ Tiger Field.

Although they didn’t achieve their altitude goal, Bruce and Team Tiger did set two new records that day. They beat the Tiger’s previous time-to-climb to 40,000 feet world record (23 minutes, 41 seconds), setting the new record at 20 minutes, 24 seconds, in both their weight class (C-1.B) and the unlimited piston engine category.

The sun was setting now; the shadows grew long. I leaned back in my chair and watched Bruce queue up another golf ball, then knock it into a beautiful arc. It spun over the water, onto his island. “What are your plans for the future?”

Bruce gently set another golf ball into place. “I really want to take that B-29’s record. It may take a new wing, high aspect ratio, longer span,” he mused. He coiled back and stroked another golf ball across the water and, squinting, watched it roll up next to the windsock.

“There’s an unlimited 3,000-meter time-to-climb record, held by Lyle Shelton. He did it in 91 seconds.”

“Almost 10,000 feet in 91 seconds?” I asked.

“Yup. I would need to get there in 88 seconds to set a new record.”

It was cooling off now as the sun slid down behind the horizon. I stood up and grabbed a spare 3-iron.

“What would it take to get there?”

Bruce rolled some practice balls my way. “700 horsepower—on alcohol.”

I took a practice swing. “Alcohol?”

“Yup. Keeps the engine cooler. It’s doable.”

Thanks to the volunteers who have put in countless hours to make the Exxon Flyin’ Tiger a success. Most have supported Bruce since the Pushy Galore days:

Crew Chief Gary Hunter

Stephen Mallett

Donah Bohannon

Bill Gottenberg

Glen Jones

Gaby Robertson

Philip Haponic

Harry Fenton

Rabbitt Staib

Mike Peters

Brian Bohannon

John Bohannon

Ernie Butcher

Jay Wickham

Philip Haponic, Mattituck’s chief inspector and the Tiger’s engine “god.” If the Mattituck Red/Gold engine is the heart of the Tiger, then Philip is the cardiologist.