Navigation Mission Challenge — West Bend Chapter 1158

By Howard Schlei, EAA 505982

December 2016 - The briefing hut goes silent. Two Army Air Corps officers step up to the big map. The target is revealed. Tense, silent crews take notes. The mission is on.

Is this a scene from World War II? If anyone got that impression, it was intentional.

But no, the scene unfolded at the EAA Chapter 1158 Navigation Mission Challenge on September 24. Participating crews were briefed, WWII-style, for a navigation mission that required them to fly a multi-leg course and photograph a “target” using only a compass, clock, and very limited pilotage. No GPS. No magenta line.

My wife, Robin, and I had the privilege of organizing our first (annual!) Navigation Mission Challenge, with the blessing of EAA Chapter 1158. We topped it off by giving the pilot briefing in vintage WWII U.S. Army Air Force officer uniforms. The real story, however, is the way this event reconnected pilots to the basics of aerial navigation.

Old School

I learned navigation as a teenager using an E6-B flight computer, a plotter, a sectional chart, and a pencil. My private pilot ground school took place at the bar (no FBO, just a bar) at the long-gone Aero Park Airport northeast of Waukesha County Airport (KUES). At 16, I got my first glimpse into an elite set of skills, a sort of private magic that promised to define me as an aviator. GPS was far in the future in those days. I eventually discovered the VOR and the ILS, and to this day I bet I could fly an ADF approach if I could find an airplane that has one. But as J. Mac McClellan pointed out in his excellent article “The Magenta Line” (Sport Aviation, August 2016), “The magenta line is the greatest advance in aviation since the gyroscope.” Once we all got our hands on it, few of us looked back.

Inspiration

The notion of setting aside my iPad and trying to navigate “old school” has been percolating in my mind for a long time. The opportunity to challenge my fellow pilots to some throwback dead (or “ded”) reckoning came in April of this past year. At the monthly meeting of EAA 1158, I presented the story of the remarkable WWII mission flown by P-38 pilots of the 339th Fighter Squadron, when they intercepted and shot down the bomber carrying Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Army Air Corps pilots, flying fighters and guided by nothing but a U.S. Navy compass and GI wristwatch, flew 650 miles at wave-top height over open ocean to arrive at a precise point at a precise moment. Why not challenge ourselves, in some small way, to perform a similar task?

The Navigation Mission Challenge

Each fall, EAA Chapter 1158 puts on a spot landing contest and chili cook-off for an afternoon of fun with food and airplanes. This year we added the Navigation Mission Challenge — not only to test our skills, but also to expand member participation beyond the pilot’s seat. We decided that each participating “crew” should consist of a pilot, copilot, and a judge. The pilot would do the flying. The copilot would assist with timing, navigation, and traffic watch. The judge would observe to ensure no GPS or electronics are used, and to verify certain key time points. (Two-place aircraft were crewed by a pilot and judge.)

We estimated a flight of roughly one hour would be sufficient to perform key navigation functions, allow us to stagger departures for safety, and still get everyone home for some chili and spot landings.

Since the Navigation Mission Challenge was open to any aircraft, we designed two flight routes. Aircraft with a true airspeed of 140 mph or higher flew the Blue Route. Aircraft slower than 140 mph flew the Red Route. This solved the problem of sequencing departures, helped ensure there was enough separation between aircraft flying the same route, and reduced the amount of time crews waited to depart, or waited for the last participants to straggle home.

We provided pilots with the true course and distance for all but the first of seven legs and also gave them departure and arrival procedures. Pilots would determine their own groundspeeds and wind-correction angles, and put together a flight log showing the estimated time they would need to reach each checkpoint.

Given the relatively short duration of the flight, we acknowledged that our pilots would be navigating over territory that most of them know intimately. West Bend Municipal Airport has a giant lake to the east (Lake Michigan) and another good-sized lake to the northwest (Lake Winnebago). Getting lost on a local flight out of KETB would be a feat worthy of Wrong Way Corrigan. So we came up with the idea of not only prohibiting GPS and electronics, but also prohibiting sectional charts (except in emergency) and taking basic pilotage off the table as well. Crews would be provided with a chart — just not a familiar chart.

Where’s My E6-B?

As this idea took hold last spring, pilots were suddenly confronted with a critical question: Where the heck did I put my old E6-B flight computer? I for one still can’t find mine, but I spotted one at a swap meet and grabbed it quickly because it came with the original instruction manual. In June, we devoted an entire chapter meeting to relearning how to use the thing — in particular, the mysterious back side where wind correction and groundspeed calculations can be conjured up.

The June E6-B refresher meeting wasn’t the only happy benefit of issuing this navigation challenge. A recently minted flight instructor in our chapter spread the word about a nifty app that calculates true airspeed, with a side benefit that it can tell you the actual — not forecast — winds aloft. In a nutshell, here’s how it works: Take your airplane and favorite GPS device aloft, fly three perpendicular legs, and write down your GPS groundspeed for each leg. After landing, enter all three values into the app to get your genuine true airspeed along with the winds aloft at the time of the test. Several participating flight crews took advantage of this in order to find out the exact true airspeed they could expect for a given power setting, giving them an edge in their navigation calculations. In addition, on the morning of the mission, we launched a “weather reconnaissance” flight an hour before the mission briefing. They performed the true airspeed calculation and brought home to us the actual winds aloft over KETB.

Mission Briefing

On the day of the event, flight crews assembled in the meeting room at EAA 1158 at KETB. At the appointed hour, my wife and I stepped to the front of the room in full 1940s-era Army Air Corps uniforms, posing as squadron commander “Major Blunder” and group intelligence officer “Major Error.” We issued a “top secret” briefing kit to each crew, containing the map, flight logs to fill out, departure procedures, and more. Right off, we informed the assembled crews that today’s mission echoed the accomplishment of those brave P-38 pilots on April 18, 1943. In our case, crews would be flying a multi-leg mission, locating a target, photographing the target, and returning to base. What’s the target? Major Error said, “Our intelligence sources have not been able to tell us what the target looks like, but we are told you will know it when you photograph it.” Hey, we didn’t say this would be easy!

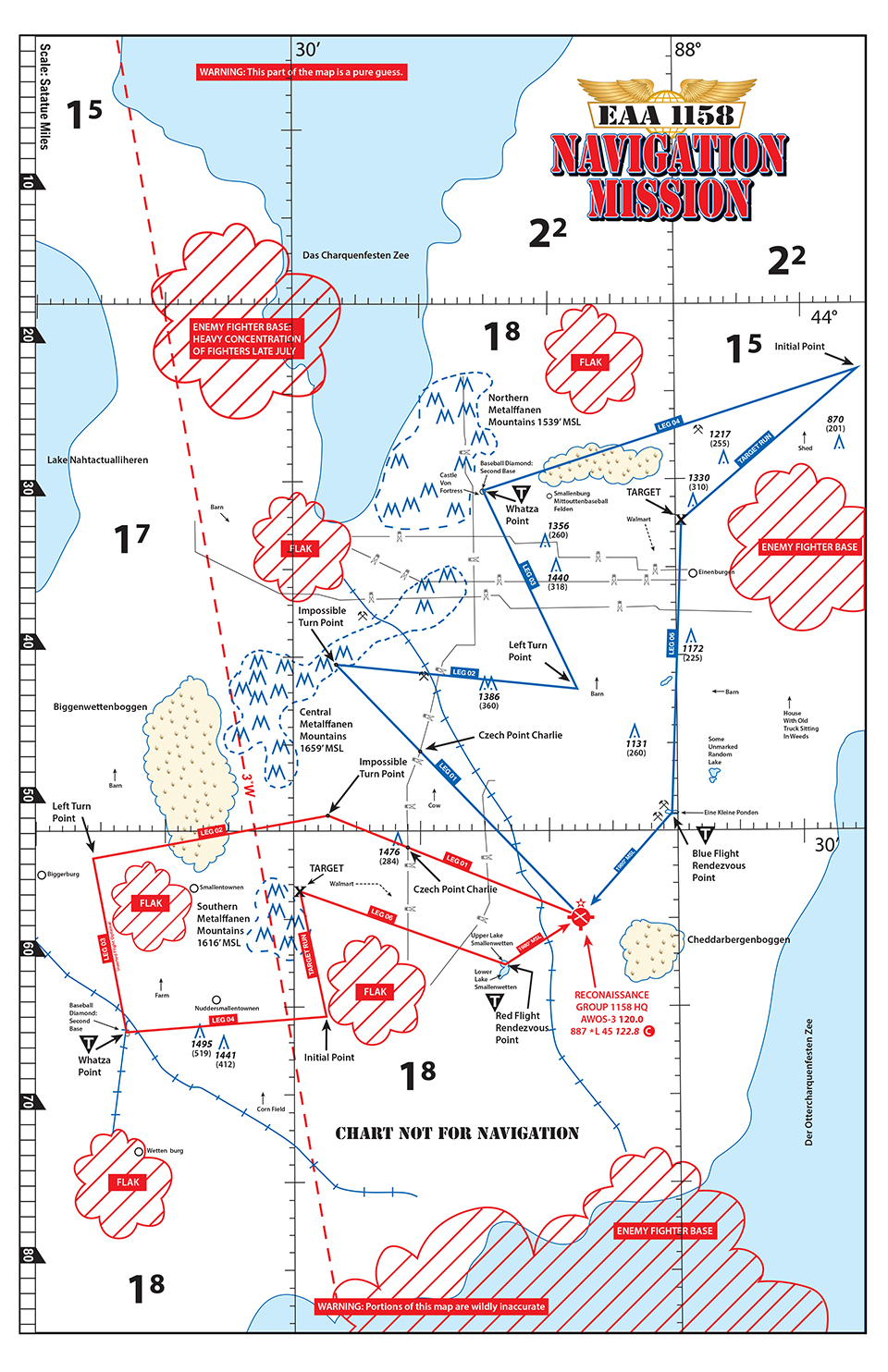

The Chart

Sectional charts were prohibited. Instead, we provided a pseudo-sectional chart. We scanned a sectional chart into a computer, then drew a new “sectional” chart with basic latitude/longitude, elevation, and obstacle information. Airports around the area were marked as enemy flak concentrations or enemy fighter bases to be avoided. Lake Winnebago was redrawn and renamed “Das Charquenfesten Zee.” Familiar towns were either not marked or renamed “Smallenburg” or “Biggerburg.” We renamed Horicon Marsh “Biggenwettenboggen.” We included very basic tools for pilotage — railroad lines and power lines — but we also threw in useless references to “cow” and “barn” and, my favorite, “house with old car sitting in weeds.” Aside from a touch of humor, the real purpose of providing a semi-bogus chart instead of a sectional was to make our pilots’ familiarity with the local territory meaningless.

The Routes

It may have been an ersatz chart, but the two flight routes drawn on the chart, Blue and Red, were precise and measurable. In fact, pilots had to pull out their old plotters and measure the true course and distance for the initial leg of their selected route (data for all other legs were provided). I personally had fun with the route planning, spending most of the summer fine-tuning the routes and checkpoints with multiple test flights in a Beechcraft Bonanza and a Rotorway Helicopter, with a tool bag including ForeFlight, GPS, satellite imagery, and even Google Maps.

For departure, pilots were instructed to climb on the runway heading to their assigned altitude and perform a kind of racetrack maneuver that would take them around and back over the airport. The intersection of the two runways at West Bend Airport formed the first checkpoint. Cross that initial checkpoint, on course, at cruise, at the assigned altitude, and begin timing.

The first leg took our crews to “Impossible Turn Point,” which was defined only by distance and true course. In other words, if you failed to get your true airspeed, groundspeed, and wind-correction angle calculations right, you weren’t going to hit the first checkpoint. Next up came “Left Turn Point,” which also lacked ground reference. After that, assuming the crew flew the first two legs accurately, it had to locate “Whatza Point,” which actually offered a ground reference — pilots had to fly over second base on a baseball diamond. From Whatza Point, pilots flew another time/distance/course leg to the “Initial Point,” where they turned to make their target run. Fly over the target, take the photo, then turn on course for the final objective, called “Rendezvous Point,” the only other ground reference point on the trip. Over the two ground reference points, Whatza Point and Rendezvous Point, pilots were required to note their time (confirmed by the onboard judge), which later factored in the judging. Rendezvous Point finished the routes a few miles from the airport, allowing pilots to set up and fly the proper pattern for landing.

Seconds Count

Both routes featured some sharp turns. In the briefing, we emphasized that seconds count — so don’t round up or down the minutes when calculating on the E6-B. We also pointed out that the end point of each leg marked the starting point for the next leg — so decide ahead of time what you plan to do to make the turn. Turns might be up to 150 degrees. How do you plan to stop timing one leg, change course, and start timing the next leg? To help out, the Top Secret Briefing Kit contained a diagram for a “128-second turn.” It offered a method for pilots to arrive over a point (stop timing), perform a maneuver built on a standard-rate turn and a 90/270 reversal, and end up over the same point on your new heading 128 seconds later (start timing). Crews could then add the 128 seconds into the overall time estimate for the route.

Scoring

In the end, only half of the six participating crews managed to find and photograph the targets (a radar dome for the Red Route and the Road America grandstands for the Blue Route). Keep in mind that they weren’t told what the target was. They were instructed to fly a course to a point and take a picture. Everybody came home with a picture, but not all had the correct picture.

The winning crew of the first ever Navigation Mission Challenge was EAA 1158 chapter member Rolf Berg and his copilot, Terry Sells. This team met the four requirements for success: 1) Successfully photographed the target, 2) held altitude within 100 feet throughout, 3) had the least amount of time difference between their estimated and actual arrival times over two required time points, and 4) returned to base. Two things are worth mentioning about our winner. First, Rolf flew the course in his Enstrom helicopter. And second, Rolf was one of the six Epic pilots who recently flew around the world, terminating the trip at AirVenture. I asked Rolf which was more daunting, our little clock-and-compass challenge or flying around the world. He replied, “Hands down, this is harder!”

Flying for Fun and Precision

The Navigation Mission Challenge yielded many happy results. Participating pilots embraced the idea of old-school navigation; several reported going out beforehand and brushing off their no-GPS navigation skills. A couple of crews reported using the True Airspeed app in advance to determine their aircraft’s performance for specific power settings. They all took on the challenge of relearning their E6-B flight computers with a mix of fear (“did I ever understand this thing?”) and surprise at how quickly it all came back to them. The crews seemed to enjoy the history and humor we brought to the pilot briefing. The structure of the event invited more of our members into the sky as copilots and judges. And best of all, we had a day of flying for fun and precision.

In the end, everyone said, “Let’s do this again!” Join us for the next EAA 1158 Navigation Mission Challenge at KETB on Saturday, May 13, 2017!