Molded Mosquito Marvel

Wooden Wonder wows in Warbirds

By Frederick A. Johnsen

July 28, 2019 - It gained the nickname Wooden Wonder for its extensive use of formed plywood, and its phenomenal speed. Some variants were unarmed — they could outrun their adversaries. The de Havilland Mosquito earned a respected place in the history of World War II aviation.

But the wood that made it light and fast was never meant for the ages. Mosquitoes slipped out of military service after the war as jets took over for speed and altitude. A few found work in the civilian world, but their numbers dwindled.

The reborn de Havilland Mosquito at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2019 is the result of a massive restoration in New Zealand by Avspecs for American warbird collector Rod Lewis. Lewis continues to grow his group of rare machines in Texas, taking them out for public air shows like AirVenture.

Some of the yellow birch used in the Mosquitoes' wartime plywood sandwich came from mills in Wisconsin, shipped to England to meet the critical need. The Wooden Wonder had 454 square feet of wing area; for comparison, the P-38 Lightning had only 327.5 square feet. The Mosquito stretched a tape measure several feet more in length and wingspan than did the American P-38 fighter, but in at least some models, the Mosquito's empty weight was only 1,500 pounds more than the P-38. And as a fast bomber, the Mosquito edged out the P-38L by one mile an hour, topping out at 415 mph at 28,000 feet. The Mosquito was no slouch in the speed department.

The world of warbirds sees aircraft move in and out of flying status. The number of flyable Mosquitoes globally is about three or four, with a few other projects in the works. A special Warbirds in Review session on Friday afternoon featured Rod Lewis' immaculate example.

Warren Denholm of Avspecs told the crowd that de Havilland Aircraft had already developed a plywood sandwich process for construction when the British government issued a specification for a warplane that de Havilland chose to answer. The Mosquito was not immediately embraced; other manufacturers were touting the virtues of aluminum structure, Denholm said. Using wood "was like turning back the hands of the clock," he added. The process for pressing the plywood in huge fuselage molds is generally a dry layup process, according to Denholm. Other wooden subassemblies could be made by British cabinet makers in small shops. This decentralized production in war-torn England and employed skilled craftspeople.

This Mosquito entered service with the Royal Air Force in March 1945. It went first to an operational training unit. By 1948 it was one of about 80 Mosquitoes purchased from England by New Zealand. Some records indicate only about 20 of the Royal New Zealand Air Force Mosquitoes were flown. This aircraft may have been part of the 60 held in storage.

Denholm told the audience that a California company bought about six of the New Zealand Mosquitoes for use in survey work in the early 1950s. But the purchase ran afoul of import issues after only one — this one — had been ferried to the U.S. The Mosquito eventually was impounded and parked outdoors at the old Whiteman airport in the greater Los Angeles area. Vandals and the weather took their toll for the next two decades. By 1971, a new owner bought the remains of the Mosquito and stored most of the carcass inside, Denholm said.

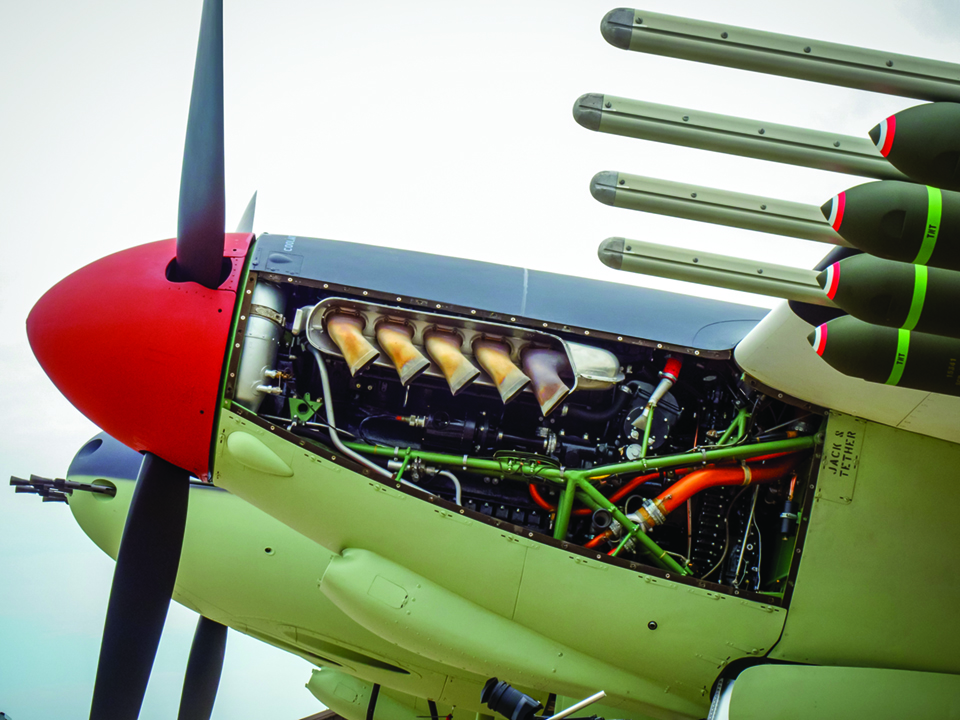

In 2014, negotiations with the owner resulted in the sale of the Mosquito so Avspecs could begin its resurrection. Surprisingly, the original Merlin engines were still with the aircraft, and these were delegated to the Vintage V-12s company for rebuilding in Tehachapi, California. The rest of the airframe, such as it was, made its way to New Zealand in a shipping container. This is the third Mosquito project undertaken by Avspecs since 2005. Denholm told the audience the first one required seven years to complete; the second one was done in five years. And this example rolled out of the shop in four years, the result of increased understanding and those vital fuselage molds made for the first airplane.

The Wooden Wonder (other nicknames include Timber Terror and Loping Lumberyard) conceals a lot of copper inside. Denholm explained, "It's full of literally miles of copper bonding strip" to bond metal parts to each other for electrical safety.

The de Havilland Mosquito earned a place in World War II history for its speed, versatility, and smooth wooden construction. The Mosquito at AirVenture 2019 demonstrates those traits.